Tanabe Helps ENA Adopt Sickle Cell Pain Guidelines

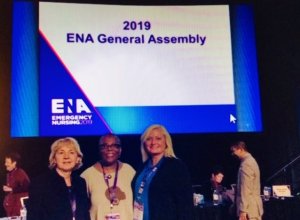

Paula Tanabe was standing in a nondescript convention center ballroom in Texas on an otherwise unremarkable Sunday morning in late September 2019. Looking back now, she describes that moment as “the highlight of my career.” What happened in that room, at the General Assembly of the Emergency Nurses Association (ENA), will change the lives of thousands of patients with sickle cell disease for years to come.

That morning was the culmination of more than a decade of research, planning and advocacy. Tanabe, the Laurel Chadwick Distinguished Professor of Nursing at Duke University School of Nursing, has been working with colleagues across the state and the nation to solve one of the most frustrating problems facing sickle cell patients: helping them receive treatment for severe pain in the emergency department. At that September meeting, the ENA took an enormous step to address that problem when it voted to adopt a resolution, drafted by Tanabe and two other emergency department nurses from North Carolina, to disseminate evidence-based guidelines and education on sickle cell treatment to all EDs in the United States.

Sickle cell disease is still as misunderstood as it is debilitating. This genetic disease affects the production of hemoglobin, resulting in misshapen red blood cells. Instead of carrying much-needed oxygen throughout the body, these “sickle cells” can get stuck in blood vessels. Organs and tissues are choked off in an enormously painful episode called a “vaso-occlusive crisis.” People with sickle cell disease can suffer through several of these crises a year, and their only recourse for pain management often comes from receiving opioids in the emergency department.

Tanabe saw the problem first-hand when she was working on pain management as an emergency department nurse and encountered patients with sickle cell disease. “As an ED nurse,” she noted, “all you see is that they come in with this horrible pain, and they need opioids – often a lot of them – to manage that pain. Patients can’t really predict when those crises are going to come, and when they do, the pain is horrible, and they need relief. So they usually have to go to an emergency department.”

It seems simple enough: a patient comes into the ED with crippling pain, so you give them the pain medicines they require. But Tanabe was seeing a complicating factor with deep social roots: approximately 100,000 Americans have sickle cell disease, and the majority of them are of African descent. “If you’re a 20-year-old black male coming into the ED for opioids, the stigma and bias against the disease in the population is huge,” said Tanabe. “Patients are being told that they’re addicted to opioids and that they’re just drug-seeking. ED providers are trying to do the right thing, but that bias is still there.”

Tanabe and her team knew that the key to dispelling this bias was making sure that all ED providers had reliable, evidence-based pain management guidelines for sickle cell patients. They surveyed the latest research, conducted new research of their own, and spoke with experts and patients from all over. “We learned more about the disease, and we met more patients to hear their stories and really understand what their life was like,” she said. Two sickle cell patients in particular, Darryl Smith and Gail Aiken, made immeasurable contributions to Tanabe’s research over these years.

After more than ten years of nationwide research, advocacy and education, it was time to create the ENA resolution. Tanabe worked with Emilia Frederick of UNC-Chapel Hill and Angie Alexander of Atrium Health in Charlotte to craft a comprehensive resolution that would transform the treatment of patients with sickle cell disease in emergency departments across the United States. The resolution lays out background information on sickle cell, and charges the Emergency Nurses Association to widely disseminate the evidence-based recommendations and other important education.

Finally, Tanabe and her colleagues were ready to bring the resolution to the ENA General Assembly in Austin. She expected the worst. “For the last ten years, all I’ve heard is negative, negative, negative,” she said. But to her shock, nearly all of the comments were in support of the resolution. She had been careful to lay the groundwork by reaching out to hundreds of colleagues at other state ENAs beforehand, but what happened next far surpassed her expectations. After a negative comment or two, one member got up and galvanized the crowd: “We should be embarrassed. Why are we even having this discussion? These individuals have severe pain, and there are evidence-based guidelines to treat it. What are we talking about?” According to Tanabe, that was the final straw. “We didn’t have to say anything else, and then the vote was 87.6% for the resolution.”

Finally, Tanabe and her colleagues were ready to bring the resolution to the ENA General Assembly in Austin. She expected the worst. “For the last ten years, all I’ve heard is negative, negative, negative,” she said. But to her shock, nearly all of the comments were in support of the resolution. She had been careful to lay the groundwork by reaching out to hundreds of colleagues at other state ENAs beforehand, but what happened next far surpassed her expectations. After a negative comment or two, one member got up and galvanized the crowd: “We should be embarrassed. Why are we even having this discussion? These individuals have severe pain, and there are evidence-based guidelines to treat it. What are we talking about?” According to Tanabe, that was the final straw. “We didn’t have to say anything else, and then the vote was 87.6% for the resolution.”

Even as Tanabe and her team celebrated this enormous achievement, their joy was tempered because two of their own weren’t there to celebrate with them. Darryl Smith and Gail Aiken had both passed away in July 2018 of complications from sickle cell disease. In an almost mystical coincidence, Aiken’s family and friends were holding a dedication service at her church the same morning the ENA resolution came up for a vote. Tanabe had become close with Aiken through their research and advocacy work, and regretted that she couldn’t be present at the service to speak about her friend. She sent DUSON Assistant Professor Mariam Kayle in her stead, and texted her with the good news only moments before. “When she got up to speak at the service, she was able to say that the resolution just passed,” said Tanabe. “The whole church clapped – it was all really emotional.”

With this transformative resolution in hand, Paula Tanabe now wants to use it to ensure that thousands of sickle cell patients get the pain treatment they need no matter which ED they walk into. “I think this will be huge,” she declares, “because when your professional organization says, ‘this is the evidence-based practice, this is what you should do,’ then you’ll make a change. The goal is to have the guidelines be as strong as possible, with great evidence to back them up. And then providers will use them and believe patients, and there should be better patient outcomes.”