Duke, Vanderbilt, and UNC Nurse-Midwives Join Forces to Reduce Black Maternal Health Risks

Having a trained and trusted professional who can help parents-to-be make healthy decisions and choose proper prenatal care can make a difference in maternal health and birth outcomes.

Editor's Note: This story was contributed by Tatum Lyles Flick, Communications Specialist, Vanderbilt University School of Nursing.

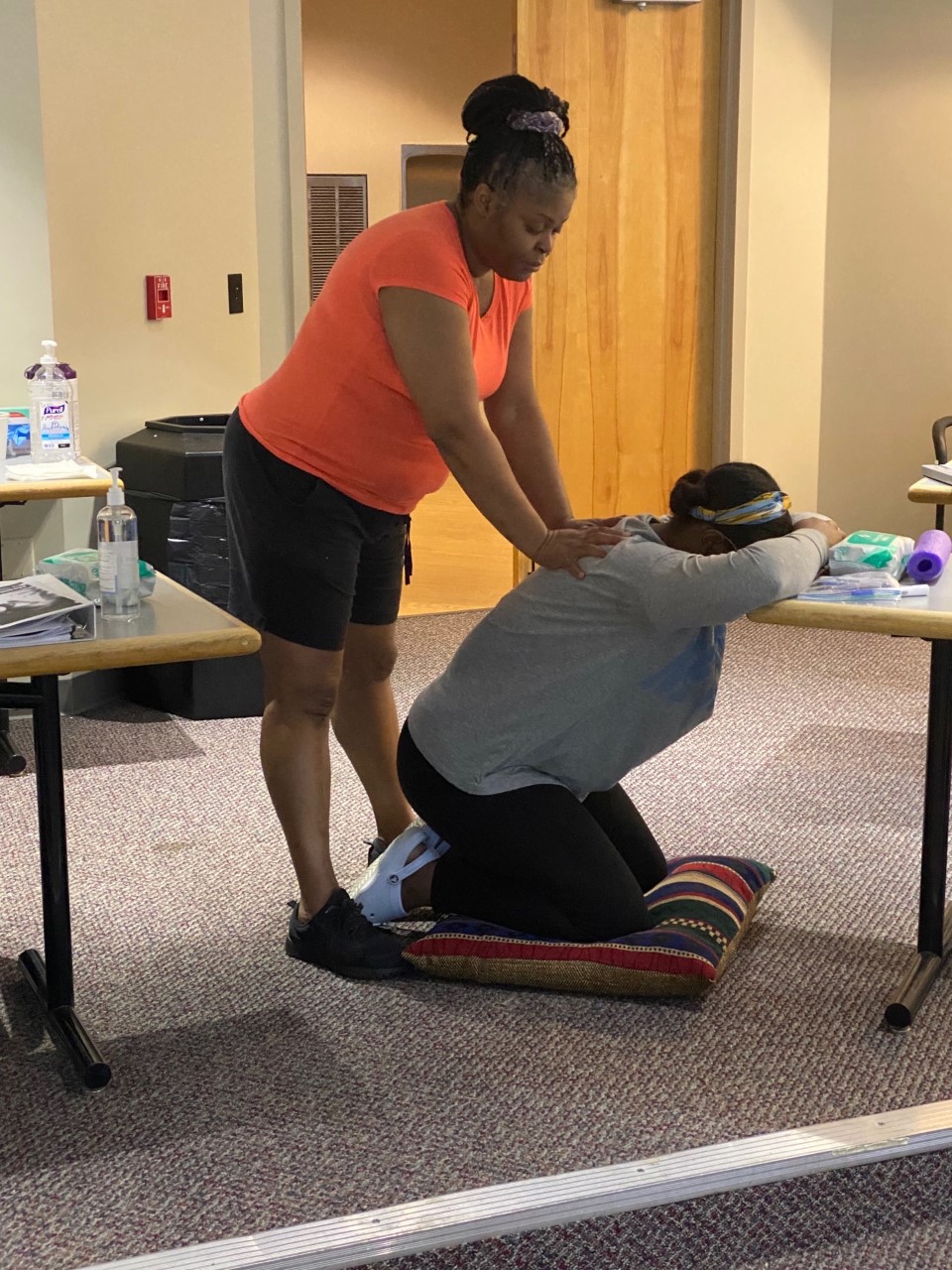

Nurse-midwives and educators from three prominent research universities have teamed up to improve pregnancy outcomes in Black communities by providing specialized training for doulas, persons who support birthing mothers and families through the entire process of childbirth.

The Alliance of Black Doulas for Black Mamas is led by Duke University School of Nursing Assistant Professor Jacquelyn McMillian-Bohler, PhD, CNM, and Vanderbilt University School of Nursing Associate Professor Stephanie DeVane-Johnson, PhD, CNM, FACNM—both graduates of Vanderbilt’s nationally-recognized Nurse-Midwifery program—and University of North Carolina School of Medicine Assistant Professor Venus Standard, MSN, CNM, FACNM. The project leaders are Black, certified nurse-midwives with a combined 60+ years of midwifery experience.

Doulas offer emotional and informational support for pregnant persons and their families. Unlike nurse-midwives, they are not medically trained; however, their help with things like breastfeeding, acupressure, birth plans and postpartum issues can be critically needed, as can their presence as an advocate for the mother.

The three researchers are addressing the U.S.’s Black maternal health crisis. The U.S. has the highest maternal mortality rate among developed countries—and the crisis is even more pronounced for Black mothers. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention statistics reveal disparities between pregnancy complications and risks across different racial groups. Black women are approximately twice as likely to have a moderately low birthweight child and three times as likely to have a very low birthweight child than white or Hispanic women. Black women are also more likely than white or Hispanic women to die from pregnancy complications—almost 67 percent of which are preventable.

Having a trained and trusted professional who can help parents-to-be make healthy decisions and choose proper prenatal care can make a difference in maternal health and birth outcomes.

McMillian-Bohler, DeVane-Johnson and Standard worked together to write and fine-tune a plan to train and provide Black doulas to help Black families, with hopes of mitigating the high Black maternal and infant mortality rate. In 2020, the doula project was funded by a $75,000 award from UNC, the Harvey C. Felix Award to Advance Institutional Priorities, and the group trained its first 20 doulas. In 2021, they received a $545,000 Duke Endowment grant, which funds the program for three years beginning in May 2022.

The main program goals are to: decrease Black maternal mortality and morbidity; improve patient experiences; provide doulas for free to families; and help those interested in becoming doulas build critical skills and later use those skills to earn wages. The program’s goals align with the 2021 Black Maternal Health Momnibus Act, which “directs multi-agency efforts to improve maternal health, particularly among racial and ethnic minority groups, veterans, and other vulnerable populations,” states congress.gov.

“The training is more than about labor and birth,” said McMillian-Bohler, who teaches the mindfulness curriculum. “We also introduce the doula to general stress-reduction techniques such as mindfulness and acupressure. Although evidence suggests these techniques are helpful, they are often not accessible to the Black community.”

DeVane-Johnson works remotely as the community engagement liaison for the program, which is housed at UNC Family Medicine in Chapel Hill, but the doulas will be serving families in Durham, Wake and Orange counties in North Carolina. Devane-Johnson hopes to receive funding to expand this program to Black pregnant persons in Nashville, TN.

“The strength of the program is the expertise of the entire team and the integration of the expertise,” said Standard, who connects families with doulas from the program and is currently teaching the third cohort of Black doulas. “Although each university could independently support the doula program with its hospital system and academic affiliation, a collaboration between the three universities positively impacts the project as a whole.”

Doula training applicants attend information sessions and are screened to make sure they will be successful in the program and that they will enjoy the work.

According to McMillian-Bohler, the program’s doula/family partnerships offer racial concordance, which can increase trust and understanding.

“I think the fact that we are able to come in and talk about some of these health resources and, I hope, remove some of the stigma, opens up a whole area of health care and wellness to people who desperately need it, who maybe didn’t feel like it was for them,” McMillian-Bohler said.

The doulas recognize that birthing parents have the right and need to speak up for their own bodies and health, and help them build the confidence and ability to do so.

To receive help from a doula in the program, a person must be Black, pregnant and planning to deliver at a University of North Carolina-affiliated hospital.

“By having a culturally concordant doula, the patient has a personal advocate, educator and support person to help guide and navigate the system as a Black person, whose needs are often dismissed or ignored,” Standard explained.

“Our hope is that by selecting doulas, who are gatekeepers into various aspects of the Black community, and by giving them tools to share with families, we create a community project that helps birthing families and doulas," said McMillian-Bohler.

The program offers doula training that is expanded to accommodate the specific needs of Black women, covering topics like reproductive justice and the “superwoman schema,” which says that many Black women care for others at their own expense, increasing stress during a pregnancy.

“The goal is to help mitigate Black maternal and infant mortality rates,” DeVane-Johnson said. “Doulas stand in the gap. Sometimes, Black women bring things up to their health care providers and are not taken seriously, or the provider does not talk at a level that the patient and family can understand. The doula is there to bridge that gap and potentially interpret information.”

"We hope to create opportunities for Black women to find their voices and be empowered to ask questions. Doulas are there to empower, uplift and elevate birthing families. If something doesn’t feel right, the doulas help them recognize that they need to speak up and keep speaking until their voice is heard."

Jacquelyn McMillian-Bohler

Assistant Professor

DeVane-Johnson also serves as the facilitator for breastfeeding lectures. She studies the history of breastfeeding and presents lectures to doula-trainees to help them understand the hurdles faced by those they are trained to help. The doulas use this training to support Black women who want to breastfeed and connect them with lactation consultants, as research indicates that breastfeeding decreases cancer risks in mothers and improves health outcomes for babies.

“Black women have the lowest breastfeeding rate out of any race,” DeVane-Johnson said. “When variables such as socioeconomic status, education and marital status are controlled for, similar positioned white women still tend to breastfeed at higher rates.”

Doulas help solve communication issues and offer consistent labor support for those who don’t have it, something that has been shown to decrease time in labor and the need for pain medications.

“We hope to create opportunities for Black women to find their voices and be empowered to ask questions,” McMillian-Bohler said. “Doulas are there to empower, uplift and elevate birthing families. If something doesn’t feel right, the doulas help them recognize that they need to speak up and keep speaking until their voice is heard.”

The doulas are trained to recognize preterm, term and postpartum warning signs that may otherwise go untreated, leaving parent and baby at risk.

They train over the course of seven weekends. While on-call with patients, they assist with birthing plans, help pack bags for the hospital and even attend appointments, depending on how much support the birthing parent needs. Once trained, a doula is paired with three Black families who receive assistance for free.

DeVane-Johnson says program applicants need to be Black, have a passion for birth work and have a desire to support women in labor. In the past, applicants may not have been financially able to secure training, but thanks to the grants, training is free. Applicants are screened to make sure they have reliable transportation, a job that’s flexible enough to allow them to leave to attend a birth and are vaccinated against COVID-19.

According to DeVane-Johnson, the most important qualification is “a passion to help support Black families in the community.”

“Being a doula often is different than what many people imagine,” said McMillian-Bohler. “They may have a romanticized notion of what the job is like. Babies come all the time, anytime, and doulas have to be able and willing to drop whatever other things they may be doing to come to a birth.”

The program benefits go beyond those received by the birthing family.

“Doulas are marketable and can hire out their services after they work with their first three families through the program,” DeVane-Johnson said. “This training will help them bring in money for their families and provide an important service.”

The program supports workforce development, DeVane-Johnson said, as the new doulas have sustainable jobs and develop entrepreneurial skills.

With many interested in training and families lining up for the service, the program is poised to make a difference in communities and in Black maternal health—and the leadership team envisions it as something that can go even further.

“Our goal with this program is to create a doula training model that can be tailored for birthing people with disabilities, those in the LGBTQ+ community, making things culturally relevant to whatever specific marginalized population that is birthing, because it’s these marginalized populations that have the worst birth outcomes,” DeVane-Johnson said.

At this time, the program has one year of data, and the group looks forward to evaluating the incoming qualitative and quantitative data, something the new Duke Endowment grant will help them do over the course of the next three years.

DeVane-Johnson, McMillian-Bohler and Standard also hope to see the program expand beyond the borders of North Carolina.

“We want to disseminate this program throughout the country,” Standard said. “We want to reach out to other academic hospital-affiliated institutions and integrate this program into their maternal care systems.”

If the program receives additional funding, Standard said they plan to increase compensation to the doulas and faculty and hire additional staff to support an expansion to help more families.

Photos courtesy of Venus Standard and Alliance of Black Doulas for Black Mamas.