Pediatric Lacerations Repaired with Compassion, without Sedation

Facial lacerations in children can be repaired without sedation using a developmentally compassionate approach, according to Duke School of Nursing instructor Becky Carson.

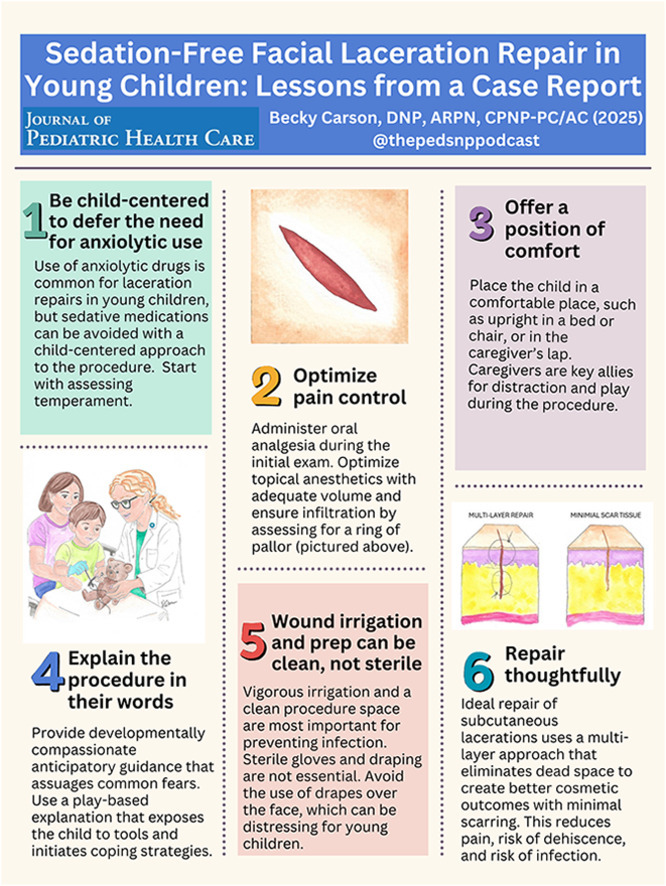

Facial lacerations are common among children, who are in the important business of playing, learning, and growing. While medical providers have routinely used sedation to keep kids calm and compliant while they repair cuts, these anxiolytic medications can carry risks for children. Duke University School of Nursing instructor Becky Carson, DNP, APRN, CPNP-PC/AC, offers an alternative method that bypasses the use of sedation, where appropriate, while minimizing distress and pain among pediatric patients.

Prevalence of Pediatric Facial Lacerations

“Lacerations are one of the most common injuries in children for many reasons,” said Dr. Carson, who is a pediatric nurse practitioner at a local pediatric urgent care and teaches in Duke’s DNP and MSN programs. “Kids play hard and lack adult-level coordination and balance. They’re developmentally curious and adventurous without a full understanding of risk—think running at the swimming pool—and their heads are larger in comparison to the rest of their body, which makes them top-heavy.”

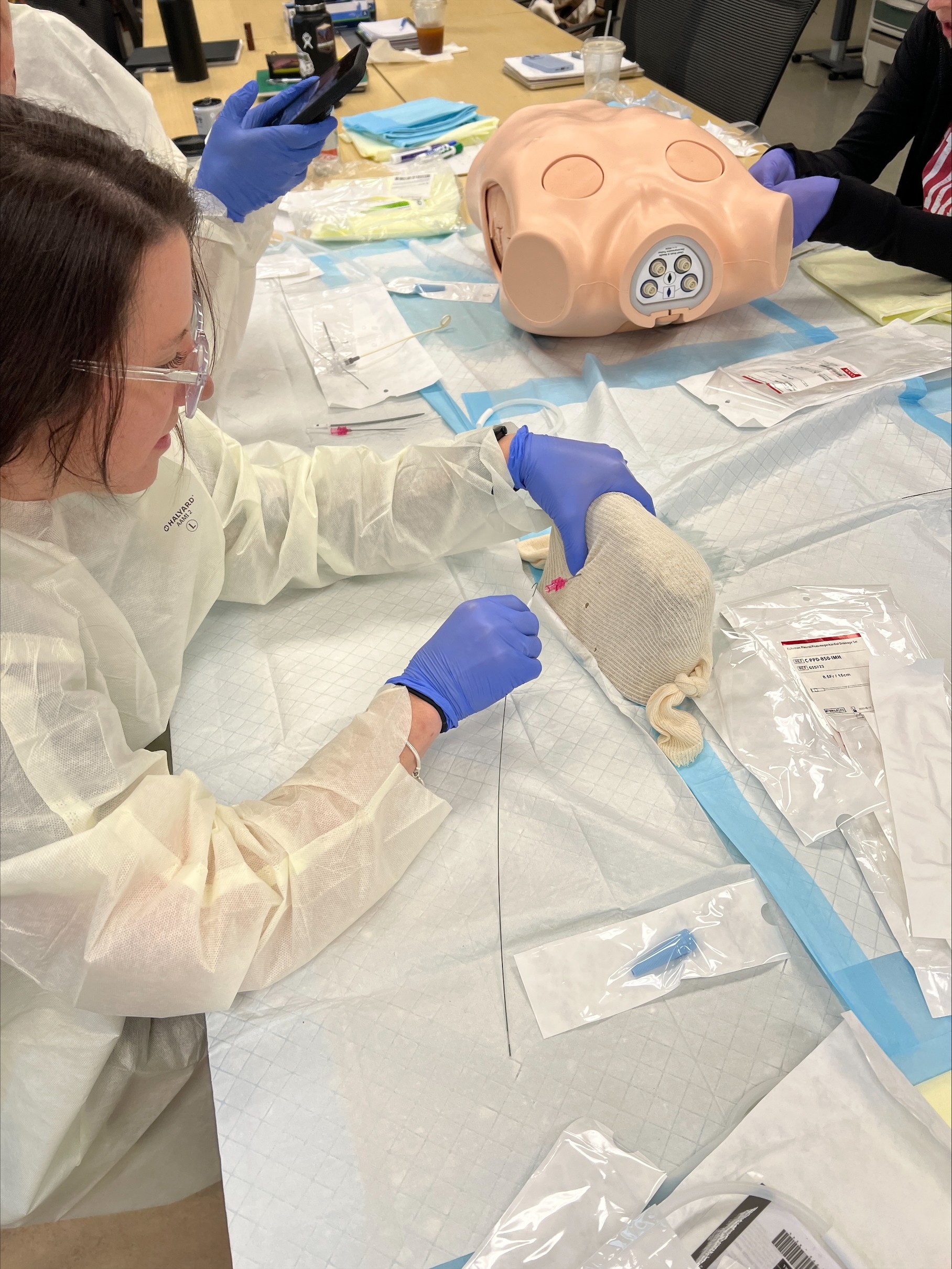

Since facial lacerations are so common, so are the procedures to repair them, but these nevertheless require a significant amount of skill. While the scientific literature has tended to focus more on the technical or procedural aspects of laceration repair, Dr. Carson saw an opportunity to better outline the emotional, interpersonal skills that medical providers can develop—which she says can cancel out the need for sedation in many cases.

Benefits of Minimizing Sedation Use

According to Dr. Carson, while sedation may still be necessary in some situations to avoid distress, it is important to develop a robust method of supporting pediatric patients and minimizing sedation where possible. Children under age six are at greatest risk of adverse events, which may include the need for medically supported breathing during the procedure, nausea or vomiting, heightened anxiety or non-compliance due to the medication’s disinhibiting effects, or lingering drowsiness that can lead to more falls if not supervised diligently.

“Avoidance of sedation avoids all of these risk factors and allows the child to return to their normal activities immediately after completing the procedure,” said Dr. Carson.

Incorporating a Developmentally Compassionate Approach

Dr. Carson advocates for what she has termed a developmentally compassionate approach when supporting pediatric patients and their caregivers through facial laceration repair. A central component of this approach is play-based “anticipatory guidance” that helps explain to the child what to expect, alleviating their fear and discomfort.

“I created the term ‘developmentally compassionate’ when describing the approach to preparing the child because you have to understand how their developmental age often determines the way children think, how they see the world, their fears, and what brings them comfort,” said Dr. Carson. “When they understand what is happening via an explanation that is sensitive to those needs, and their pain is eliminated, they can become easy partners in the repair.”

In a case study published in the Journal of Pediatric Health Care, Dr. Carson provides a table with examples of dialogue that can be used with a child to calm them, build rapport, and foster understanding. She outlines her experience treating a pre-school aged child whom she said tolerated a laceration repair procedure well and “had an excellent outcome both cosmetically and psychosocially” because of the methods she employed.

"Because the child was without pain, comfortable, and trusted me, I was able to close the wound with the advanced suture techniques that promote healthy wound healing,” said Dr. Carson.

In her case study, Dr. Carson affirms that “pediatric-focused nurse practitioners are excellently positioned to be clinically competent, expert proceduralists capable of building rapport with children and caregivers.” She hopes that her recommended approach—which she says has never been fully described in the literature until now—will go a long way in easing laceration repair for both children and their caregivers.