IDEAS for Hope: Integrating Suicide Prevention into HIV Care in Tanzania

Duke Nursing faculty member Brandon Knettel, PhD, discusses an intervention he led to address high rates of suicide among people living with HIV in Tanzania.

Brandon Knettel, PhD, Associate Professor at Duke University School of Nursing and Associate Director of the Duke Center for Global Mental Health, recently completed a four-year grant-funded research project in Tanzania, where he partnered with medical providers and patients living with HIV to set up a nurse-led telehealth counseling intervention. The project is called IDEAS for Hope ("Addressing suicidal IDeation through HIV Education, advancing treatment Adherence, and reducing Stigma for renewed Hope among people living with HIV").

In a question-and-answer session, Dr. Knettel discussed pairing suicide prevention with HIV care, how his team tailored this intervention to Tanzania’s healthcare system, and his hopes for future research.

What is the benefit of integrating suicide prevention directly into HIV care?

We know that even though life-saving treatment for HIV has improved dramatically, people living with HIV are at higher risk for suicide due to a variety of associated social challenges, stigma, and stress. So, HIV care is an important setting for suicide risk screening and improving access to mental health treatment.

How or why was telehealth counseling selected as the preferred intervention in this case?

Tanzania has done a wonderful job of decentralizing HIV care beyond the big hospitals and into small community hospitals and clinics. The challenge is that there are only 55 psychiatrists and psychologists in the entire country, so we're nowhere near ready to put a mental health provider in each of these smaller HIV clinics. Instead, we've asked the HIV nurses to ask a few quick screening questions and then use telehealth to connect people experiencing suicidal thoughts to mental health providers in the region.

In what ways is your intervention, IDEAS for Hope, adapted to the cultural setting and healthcare infrastructure of Tanzania?

Fairly quickly, we recognized that HIV nurses were already at capacity in providing high-quality HIV care to so many people. About 4.5% of the adult population in Tanzania are living with HIV. So, asking nurses to spend hours of their day providing additional mental health support to such a large number of patients was not feasible. But they did recognize the mental health needs of their patients, so they were very willing to ask the brief screening questions and help patients to make a telehealth call. As for the intervention itself, we developed this intervention from the ground up, using elements of other evidence-based treatments, but really informed by partnering with Tanzanian providers and patients from the very beginning to create a uniquely Tanzanian intervention informed by local coping strategies, preferences, and lived experience. For example, we incorporate storytelling to examine common narratives about stigma and how they relate to the participant's experiences as a way to both normalize experiences of stigma and challenge self-stigmatizing attitudes.

What were some major takeaways? Were there any surprises?

We were optimistic that a counseling intervention had the potential to bring a lot of benefit to this community, but we were actually surprised by how huge the benefits were. In the first pilot trial of IDEAS for Hope, we enrolled 60 people who were living with HIV and had experienced recent suicidal thoughts, 30 of whom received the full three-session intervention and 30 of whom received one brief safety planning session. Three months later, only seven still had suicidal thoughts, an 88% recovery rate, and none had a suicidal plan, intent, behavior, or attempt. Our other main outcome, HIV treatment adherence, also improved dramatically, with 53 out of 60 participants either maintaining or newly achieving positive adherence three months after enrollment. We were interested to find that these improvements in suicide risk and HIV treatment adherence were not only very strong in the IDEAS for Hope group, but also in the comparison brief safety planning group. It seems like, in a place where so few counseling resources are available, even a brief session has the potential to have an enormous benefit. So, for the next step, we're preparing for a larger clinical trial to see whether a single brief session is adequate or whether our more intensive three-session version provides additional or longer-lasting benefits.

How might IDEAS for Hope be scaled out, or your research otherwise expanded?

Our long-term goal is that this can become a scalable model that we can expand throughout Tanzania and to other under-resourced areas of the world where mental health treatment is hard to access. We have already had discussions with DUSON partners at the University of Rwanda about potential expansion there, and there have been some exciting examples of interventions developed in low- and middle-income countries being adapted back to the United States, where we have our own challenges with mental health treatment access. That's an avenue we would love to explore.

Can you tell me about the framework that guides your work and how it was chosen/formulated?

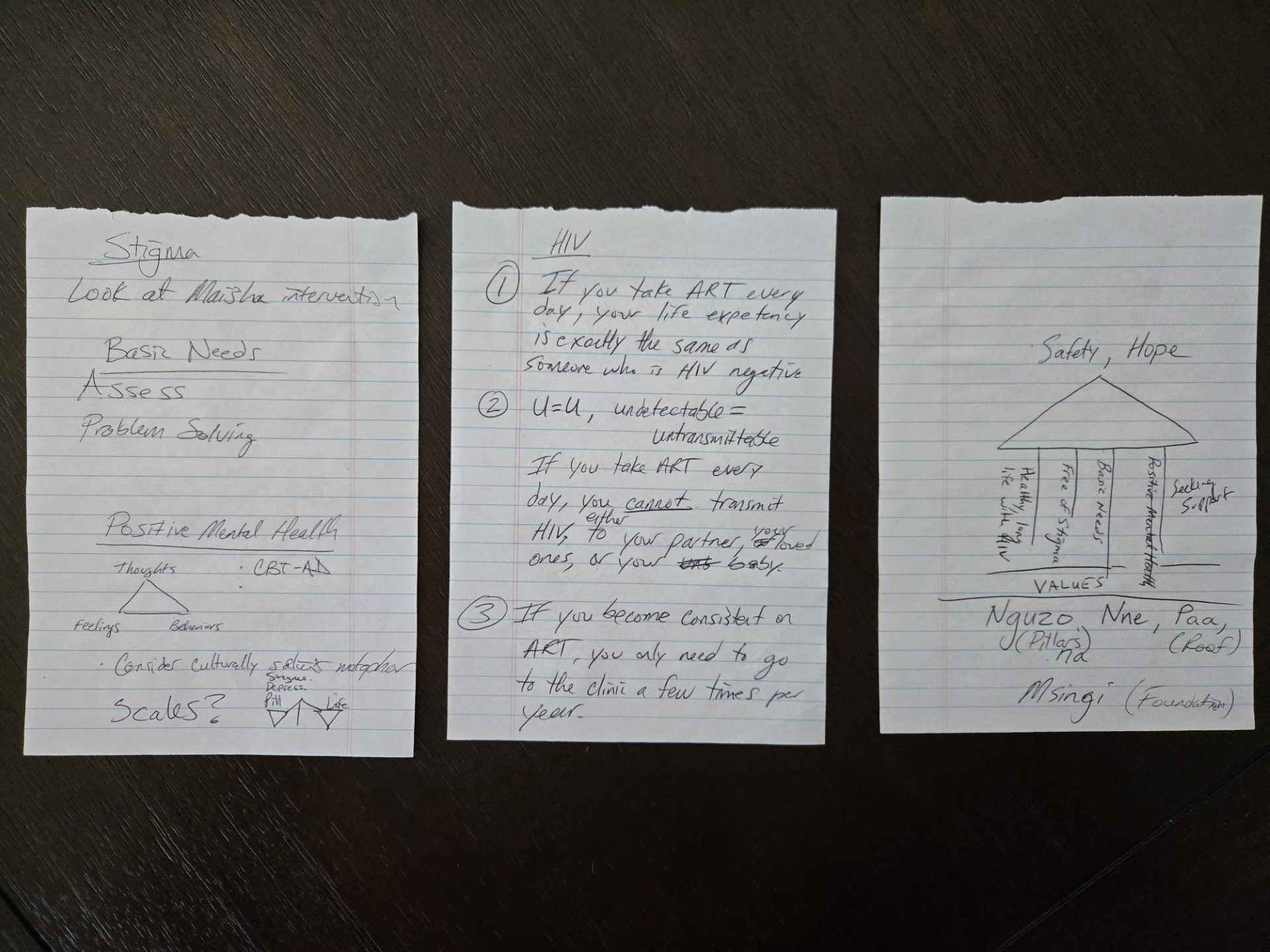

The 4 Pillars framework is really the starting point of what we wanted to accomplish in IDEAS for Hope. It is the first visual aid that we show to our participants at the start of the first session. It shows a small hut protected by a roof made up of feelings of safety and hope for the future, held up by four pillars of living healthy with HIV, becoming free of stigma, meeting your basic needs, and seeking social support, all standing on a foundation of the person's unique core values and reasons for wanting to live.

There are these urban legends of people sketching out an idea on a napkin that later became an invention or innovation, but that's basically what happened with the 4 Pillars. I was living in Tanzania for an NIH Fogarty Global Health Fellowship and was called back to Duke when the COVID pandemic hit, which is when I first came to DUSON to start my faculty position. My good friend, mentee, and colleague Ismail Shekibula had come from Tanzania to start a Master's in Global Health here at Duke. We met in my office and started sketching out our thoughts on a note pad, and the 4 Pillars model was born.

Former Dean Marion Broome and now Dean Michael Relf saw something in my program of research that they felt was a good fit for DUSON. I think they appreciated the combination of a nurse-led intervention, mental health, and global health, and felt I could bring something positive to DUSON. As a first-generation college student, a faculty position at Duke was a dream come true for me. I feel so grateful for that opportunity and have been motivated to live up to the trust they placed in me by giving back and focusing on research that has real world benefits in advancing health equity.

Dr. Knettel and his team have published 11 journal articles related to this research, most recently in JAIDS: Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, with plans to publish three more.